IL TROVATORE BACKGROUND NOTES

Between 1840 and 1853, Giuseppe Verdi was remarkably prolific, composing nearly one opera per year during what he called his "years in the galley." This intense period of labor brought him both artistic acclaim and financial success. The final three operas of this era - Rigoletto (1851), Il trovatore (1853), and La traviata (1853) - cemented his status as the most performed composer in the world.

Verdi was intrigued by the drama El Trovador by Garcia Gutierrez, the foremost Spanish dramatist, and proposed it to the experienced librettist Salvadore Cammarano, who had written the librettos for Lucia di Lammermoor and Luisa Miller, among others, and with whom he'd discussed his ultimately unfulfilled dream of a King Lear opera. Cammarano hesitated, and Verdi became frustrated. "Does he like it or doesn't he? Verdi wrote to a mutual friend. When Cammarano finally responded, he was full of reservations, to which Verdi tried to respond, even offering to consider a different subject.

Work on Il trovatore began in 1850 but proceeded slowly. Verdi first focused on a commission for Venice which became Rigoletto. He was also increasingly occupied with managing his estate at Sant'Agata. Despite these distractions - including a battle with the censors - Rigoletto was a triumph and Verdi was ready to work on Il trovatore.

Rigoletto had been a break with many of the 19th-century operatic conventions. "I conceived Rigoletto almost without arias, without finales, but only an unending series of duets..." he wrote to a friend. He hoped for something similar with Il trovatore. To Cammarano he wrote: "If in opera there were neither cavatinas, duets, trios, choruses, finales, et cetera, and the whole work consisted, let's say of a single number, I should find that all the more right and proper. For this reason, I would say that if you could avoid beginning with an opening chorus (all operas begin with a chorus!) and start straightaway with the troubadour's song and run the first two acts into one it would be a good thing..."

To Verdi's disappointment, the libretto that Cammarano delivered had all of the elements that Verdi had hoped to avoid. It began with a chorus and then a solo for the soprano and it had all the set pieces that were traditional to Italian opera. Verdi complained to the librettist but eventually decided to move forward, a move complicated by the death of Cammarano in July 1852. It was a deep personal and professional loss for Verdi.

With final tocuhes to the libretto by Leone Bardare, Il trovatore premiered in Rome in January 1853 and was a triumph. It quickly made the rounds of the European theaters, with first performances in New York and London in 1855.

Although Il trovatore remains popular today, the story has become one ripe for censure and parody (one of these is H.M.S. Pinafore). Some feel the story requires qualification or even apology.

One wonders why. One element that is often cited is Azucena's actions prior to the start of the opera. Yet are her actions that unbelievable? A woman, mentally unstable, stricken with the grief of having seen her mother burned at the stake and bent on fulfilling her mother's wish to be avenged, loses control and commits an unspeakable act. There have been similarly horrible tragedies in the news in recent years, and half of what Hollywood produces these days is more implausible.

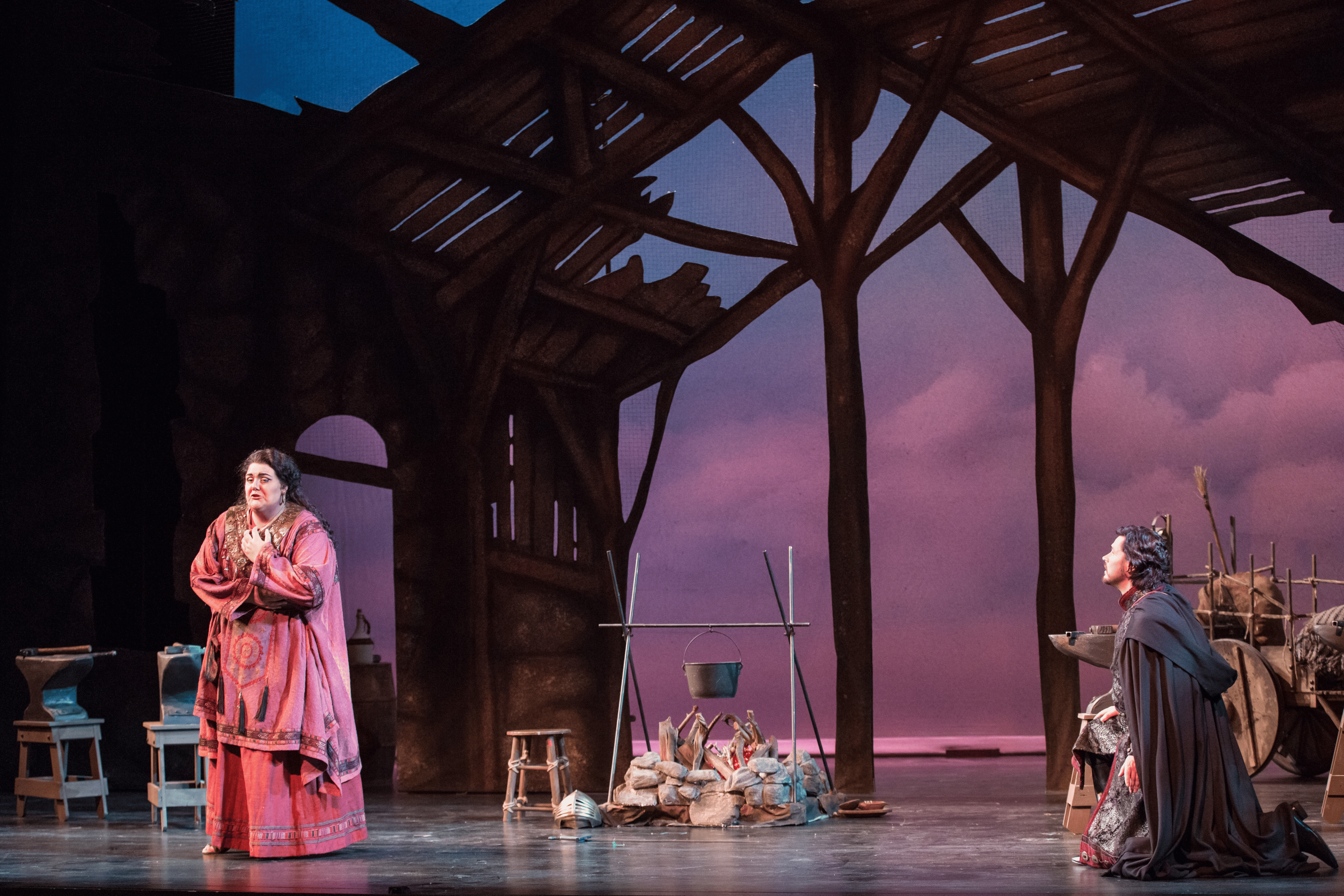

The difficulty of Il trovatore's libretto lies in the fact that most of the action takes place before opera or off stage, with the principals left to recount what has already occurred. Yet, Verdi has used this opportunity to create some of his most wonderfully descriptive music. Azucena, the character who most intrigued Verdi, also spurred his musical imagination to considerable heights. Her initial song ("Stride la vampa") contains musical and instrumental devices that vividly illustrate the funeral pyre in her mind's eye. "Condotta ell'era in ceppi," the scene in which she describes the terrible events of that fateful night, is a unique musical narrative, unlike anything in Verdi's output to that point. Even the most conventional operatic structures in Il trovatore, Leonora's "Tacea la notte" for instance, inspired Verdi's creativity to write one of the greatest soprano cavatinas in the repertoire.

What is unequivocal is that it is Il trovatore's music that has captured the opera lover's imagination. The score is rich with moments that challenge even the best operatic voices, making the achievement of surmounting these obstacles even more exciting to audiences. Tenors dread and enthusiasts clamor for the extraneous but now mostly obligatory high C in "Di quella pira" The other roles offer similar challenges to even the most accomplished artists. Caruso once claimed that to produce Il trovatore you needed "the four greatest singers in the world."

During Verdi's lifetime Il trovatore was the most popular of his works. Writing to a friend, Verdi said that "in the heart of Africa or the Indies you will always hear trovatore."

- Richard Russell